CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

ROBERT B. PARKER

Robert Brown Parker (geboren am 17. September 1932 in Springfield, MA, gestorben am 18. Januar 2010 in Boston) war ein US-amerikanischer Krimi-und-Western-Autor. Er war nicht nur der Erfinder der Cole & Hitch Reihe, der Jesse Stone-Reihe, oder der Sunny Randall-Reihe, seine bekanntesten Romane drehten sich um den Bostoner Privatdetektiv Spenser.

Parker wurde in der Hauptstadt von Massachusetts, Springfield geboren und wuchs in einem ärmlichen Stadtteil der zum großen Teil von Afroamerikanern bewohnt wurde, auf. Zuerst war er Fan von den Brooklyn Dodgers, als diese aber nach Los Angeles zogen, wandte er sich den Boston Red Sox und war seit jeher Fan und Teil der "Red Sox Nation".

Sein Kindheitsheld war Jackie Robinson, der erste afroamerikanische Baseballspieler der es in die MLB schaffte und die Rassenschranken durchbrach. Ihm widmete er später den Roman "Double Play".

In den 50ern heiratete er seine Sandkastenliebe Joan Hall. Er kannte sie schon wo er noch ein Kleinkind war und später wo beide am Colby College in Maine studierten, trafen sich beide wieder. Dort erhielt Parker auch ein Diplom.

Danach diente er im Korea-Krieg. Wie sein Protagonist Spenser.

Nach verschiedenen Berufen, wurde er dann letztendlich in 70ern ein Schriftsteller. Sein erstes Werk war eine Dissertation über Hammett und Chandler, seinen Lieblingsautoren.

---

Robert Brown Parker (September 17, 1932 – January 18, 2010) was an American crime and western fiction writer. He was not only the creator of the Cole & Hitch series, the Jesse Stone series, or the Sunny Randall series, his most famous novels are about the Boston based P.I. Spenser.

Robert was born in a poor neighborhood in Springfield, the capital of the state Massachusetts. He grew up with many African-Americans and was first, a fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers. When they moved to Los Angeles, he affiliated with the Boston Red Sox and became a part of the "Red Sox Nation".

His childhood hero was Jackie Robinson, he was the first African American baseball player in MLB history. Jackie breaks the color barrier and has made history.

In the 50's Robert married Joan Parker. He knew her since she was a toddler. They met each other again at Colby College in Maine, where Parker has earned a degree.

Then he served as a soldier in Korea, like his protag Spenser.

After various jobs, he became a writer in the early 70's. His first work was a dissertation about Chandler and Hammett, his personal favorite authors.

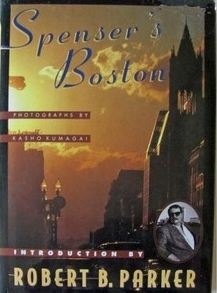

Spenser's Boston - von Robert B. Parker

Robert B. Parker - der "geistige Vater" von Spenser schuf einen historisches Begleitbuch zu seiner Roman-Serie über Boston, es zeigt ein schönes Geschenk Buch über die Stadt durch die Augen eines seiner berühmtesten Bürger - Spenser, der harte Kerl, der sensibel und intelligent ist - mit beeindruckenden Fotos und Auszüge aus den meistverkauften Kriminalromanen. Begleiten Sie Spenser, der Ihnen seine Stadt näherbringt und Orte, die Spenser höchstpersönlich empfiehlt.

Documenting historic Boston, a lovely gift book shows the city through the eyes of one of its most famous citizens--Spenser, the tough guy who is sensitive and intelligent--with stunning

photographs and excerpts from the best-selling mystery novels.

Vorworte/Einleitungen/Nachworte (Prologue's, Introductions, Epilogue's)

Parker hat nicht nur Sachbücher oder Romane geschrieben.

Für manche Bücher, besonders jene wo das Thema für ihn interessant war, schrieb er sogar die Vorworte, die Einleitungen oder die Nachworte.

Boston: History in the Making (Einleitung und eine Kurzgeschichte von Robert B. Parker / Introduction and a Short Story by Robert B. Parker)

Woman In The Dark von/by Dashiell Hammett (Vorwort von Robert B. Parker / Foreword by Robert B. Parker)

Zu 3 weiteren Büchern hat Robert B. Parker auch noch Vorworte geschrieben:

Backfire by Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler's Unknown Thriller: The Screenplay of Playback

The Best American Mystery Stories

Interview zu seinem Spenser Buch "The Professional" (2009)

Quelle: amazon.com

Sue Grafton and Robert B. Parker: Author One-on-One

In this Amazon exclusive, we brought together blockbuster authors Sue Grafton and Robert B. Parker and asked them to interview each other.

Sue Grafton is the New York Times-bestselling author of the beloved Kinsey Millhone mystery series, which continues to delight millions of readers across the globe. Read on to see Sue Grafton's questions for Robert B. Parker, or turn the tables to see what Parker asked Grafton.

Grafton: During

your career, you've generally worked as a solo writer. Aside from your collaboration with Raymond Chandler (quite dead), how did you enjoy the experience of writing with your wife, Joan? I

notice a long break between Three Weeks in Spring, which was published in 1978, and

A Year at the Races, which was published in 1990.

Grafton: During

your career, you've generally worked as a solo writer. Aside from your collaboration with Raymond Chandler (quite dead), how did you enjoy the experience of writing with your wife, Joan? I

notice a long break between Three Weeks in Spring, which was published in 1978, and

A Year at the Races, which was published in 1990.

Parker: Joan is an idea person more than a writer. She has done a lot of uncredited thinking for me. But Three Weeks in Spring, about her first bout with breast

cancer, was a special case. And A Year at the Races, also nonfiction, was about our initiation into the world of thoroughbred racing. I have found it wise for me to write and Joan to

think (egad, what if it were the other way?), but I have also found it wise not to speak for her. I liked working with her. In fact, I like pretty much everything with her.

Grafton: I notice in your bibliography that you wrote a nonfiction book called Parker on Writing. I'd be interested in reading it, but I decided I couldn't afford the $499.99 the book is selling for online. How do you feel about a reprint? (P.S.

This is not a sly hint that you should send me a copy….)

Parker: Parker on Writing is a collection of random items loosely about writing that Herb Yellin at Lord John Press collected into a finely manufactured limited

edition. Herb is a friend, and given what he paid, I can convincingly say it was affection not money that captured me. I feel fine about a reprint…. If I have an extra I will send you one,

but I'll have to look—it’s quite possible that I don't.

Grafton: I'm curious about your experience in writing Chasing the Bear: A Young

Spenser Novel. What prompted you to write about Spenser's early life? Did you learn things about him you hadn't known before?

Parker: My publisher, agent, and wife all wanted me to try a YA novel. I did three, culminating, at my publisher's request, with Chasing the Bear. Since I knew a great deal

about Spenser's adulthood, it was mostly a matter of jacking up the adulthood and sliding a consistent childhood under it. YA novels are hard because you know a great deal that you can't

use.

Grafton: I saw the movie Appaloosa last night on DVD, and while I haven't had a chance

to read the novel and study the two side by side, I got the impression that the movie was close to what you had in mind. Will you write about Virgil Cole and Everett Hitch again? You did seem

to leave the door open to that possibility.

Parker: I’ve written two sequels to Appaloosa (Resolution and Brimstone) and am finishing up a third (Blue-Eyed Devil). Ed

Harris did a wonderful job, I thought, with the movie. It is as close as it could possibly be to the book, and those parts that had to be added are hard for me to tell from my own stuff.

Harris is genius, as is Viggo [Mortensen]—they nailed the characters and the relationship. You can also take Ed Harris's word—in your own adventures in Southern California you may have

noticed how infrequent that is. Incidentally, Bragg's lawyer in the courtroom scene was played by the great Daniel T. Parker.

Grafton: How do you spend your time when you're not writing? Hobbies? Leisure activities? I'm not very good at having fun, but I'm hoping you are. Please advise.

Parker: My friend John Marsh once remarked, "I hate fun." I concur. Mostly, I just live my life, which turns out to be fun. I work out, box with a trainer, watch ball games, go out

to dinner with Joan. You've met Joan. We’ve been married fifty-three years. Now that's fun.

TELEFON - INTERVIEW / PHONE INTERVIEW

Leider kann ich nicht sagen, wann dieses Telefon - Interview geführt wurde.

Ich bedanke mich bei "Carol Baldwin", Mitglied des "Tom Selleck Forums" für diesen tollen Fund:

Unfortunately I can not say when that phone

- interview was conducted.

I thank "Carol Baldwin," Member of "Tom Selleck forum" for this great find:

http://www.podcasts2.com/podcasts/phunkin060831-ParkerM1.wma

BILDERGALERIE / PICTURE GALLERY

At Home With Joan Parker - Death and the Private Eye

Quelle / Source: http://www.nytimes.com

Joan and Robert Parker each had their own apartments in their home, using some spaces, like the first floor living room, to entertain. More Photos »

By JOYCE WADLER

Published: July 7, 2010

Multimedia

Trent Bell for The New York Times

The couple’s Victorian home in Cambridge, Mass. More Photos »

AND now, the Ballad of the Sad Chair and How It Was Tamed and Returned to Happy Domestic Life. The teller is Joan Parker, the widow of Robert B. Parker, the best-selling mystery writer who died in January.

Ms. Parker is more than a widow, of course: she is a powerhouse fund-raiser for people with H.I.V. and AIDS, a former professor of early childhood education, a woman so bold and fit that this spring, at age 77, she ascended to the top of the Big Apple Circus tent in a trapeze harness for a charity event. One cannot read a story about the Parkers without learning that Ms. Parker was the model for the independent and brainy girlfriend of Robert Parker’s Boston private eye, Spenser, or that she stays fit by running the stairs at Harvard Stadium.

But we are talking about the hole that appears in one’s life after the death of a partner — in the case of Ms. Parker, after 53 years of marriage — so widow it will be.

The Parkers had an unconventional marriage. They lived together, but separately, he on the ground floor of their Victorian house, she on the second floor. They had separate kitchens and bathrooms and, to a great extent, led separate lives. She was at charity functions most weeknights; he preferred staying in and watching baseball games with his German shorthaired pointer, Pearl. Mr. Parker had three German shorthairs named Pearl; when one Pearl died, he replaced it with another.

Ms. Parker liked to tell him, “When I go, just find a woman my height, with my color hair, call her Joan and I will live on.”

After Mr. Parker died this winter at his desk, following a heart attack, there were those who told Ms. Parker she was luckier than most, that the separate accommodations were a rehearsal for widowhood. They were partly right, Ms. Parker says. She does not have to adjust, say, to not seeing her husband puttering about the kitchen because she had her own kitchen.

Still — and we are trimming some of what comes out of her salty mouth — it has been extremely painful. Which brings us to the last months of Mr. Parker’s life, when Ms. Parker could see that, despite sticking to his 10-page-a-day writing schedule, he was failing; the heart disease he had had for years was taking its toll.

“There was one chair in his kitchen, a leather wingback chair,” she says. “I would go downstairs and feed the dogs in the morning, and in the last couple of months he would sit in the chair and stare at me. He would be sort of hunched up and looking glum. I would say, ‘Bob, you’re just staring at me, hon,’ and he would say, ‘I know.’ I’d say, ‘Do you want to talk to me or something?’ He’d say, ‘No, I just want to look at you.’ After his death, that chair was so symbolic of a sad Bob that I would think, ‘What am I going to do with this chair?’ ”

Ms. Parker began to think of it as the Sad Chair. Then one day, an architect friend showed her how to tame it. Beginning with the chair, he rearranged the furnishings that were bruising her every time she entered a room. Because even in unconventional relationships, possessions have power — particularly after a death. You take control of them, or they control you.

SOME people are more the marrying kind than others. Joan Parker, coming of age in New England in the 1950s, did not want to marry. She wanted to work. This may have been because her own experience of family life, growing up in the Boston suburb of Swampscott, had been oppressive. Her father, after she showed some athletic ability, kept her on the golf course from dawn to dusk.

She met Robert Parker at a freshman dance, when they were at Colby College in Maine, and she did not like him one bit. He was much too fast, and as they danced, his hand drifted down to her behind. Nonetheless, they became good friends.

It was not until their senior year that he told her he had loved her from the moment he saw her. Ms. Parker was reluctant, as she feared ruining the friendship. But Mr. Parker was the smartest man she knew, and she could talk to him. They married, settled in a Boston suburb and had two children, David and Daniel. Mr. Parker worked in advertising, and Ms. Parker was an extremely unhappy housewife.

Today, sitting in her second-floor dining nook, wearing form-fitting black yoga clothes, with Pearl the dog never far away, she recalls vividly how miserable she felt as a young mother, sitting on the sofa with a screaming baby while her husband went to work.

“Bob could be very emotional,” she says. “I would see Bob, in his suit and hat, crying as he goes to work, because what he wants to do is stay home and take care of baby David. I’m crying along with baby David, because all I want to do is be in the car, going to work.”

One suddenly notices something entirely unrelated to the conversation in the doorway behind her head.

Is that a chinning bar? the reporter asks.

“Yes, it is,” Ms. Parker says.

Eventually, she earned a graduate degree in childhood education and became a professor of child psychology at Endicott College and the director of curriculum and instruction for public schools in northeastern Massachusetts.

Mr. Parker, who had left advertising to get his Ph.D. in literature, began teaching at Northeastern University, and published his first Spenser novel in 1973, introducing the wise-guy private eye, a onetime boxer deeply in love with a psychoanalyst named Susan Silverman. Ms. Parker had breast cancer, then a double mastectomy. Then, in 1982, with both sons grown and out of the house, the couple separated.

A great part of the problem was that Ms. Parker felt smothered.

“I’ll give you an example,” she says. “I’d be going to the store to get some bread. He’d say, ‘Can I come with you?’ I’d say, ‘But I’m just going to buy bread.’ He’d say, ‘Yeah, but can I go with you?’ And never mind working late, never mind the overnight trips, there were a million things to explain.”

Husband and wife separated, each went into therapy.

But they missed each other, and after two years embarked on what they called their second marriage. In 1986, they bought this 14-room Victorian, paying $850,000. Ms. Parker took the third floor, which had a separate entrance at the side. Mr. Parker took the second floor, setting up his office beside the front door. The big question from most reporters involved sex.

“Are you intimate?” Mr. Parker was asked on a British talk show.

“Enough to make you blush,” Mr. Parker said.

And yes, monogamy was part of the arrangement.

In 1998, after Mr. Parker had knee surgery, there was a $1 million house renovation. Mr. Parker, an enthusiastic cook, moved down to the first floor, where he had a large kitchen. A devoted baseball fan, he decorated his bedroom with a wall-size poster of Ebbets Field that he had found and framed — one of the few decorating efforts Ms. Parker can recall him making. (If you wonder why a Bostonian cared about a Brooklyn ballpark, Ms. Parker can explain: When her husband was a boy in Springfield, Mass., the New York radio signals were the ones that came in strong, and he was passionate about the Brooklyn Dodgers.)

During baseball season, Mr. Parker fixed himself dinner and sat at his kitchen counter, watching television. The first floor, which had a large dining area adjoining Mr. Parker’s kitchen and a small living room, was where the Parkers entertained.

Ms. Parker’s second-floor apartment had a much smaller kitchen, a large bedroom made into a walk-in closet and a silver bathroom with stainless steel vanities and tub. The third floor was for guests.

Their second marriage, Ms. Parker says, was great. They pursued their own interests on their own schedules. Mr. Parker wrote, met with his trainer and stayed in. Ms. Parker rose early, did power yoga, Pilates or the stadium steps, then had fund-raising meetings. Both their sons are gay, and Ms. Parker became very involved with organizations dealing with gay rights and AIDS. The couple spent weekends together, meeting friends for dinner or entertaining.

In the last year, Mr. Parker began to have health problems: there were concerns about asthma and allergies, and around New Year’s a change in medication caused him to faint and he fell, bleeding on his bed. There were also the episodes in the kitchen, when he stared at Ms. Parker as if he knew time was short and he was trying to drink her in.

One day in January, she popped into his office at 9 a.m. as usual, before heading out for yoga.

“Bob was at his desk,” she says. “I said, ‘How are you today?’ He said, ‘Good, good.’ I came back, and I found Bob still in his chair. I went through the motions of C.P.R. and 911, but I knew he was gone.”

In the weeks that followed, Ms. Parker tried to adjust to a house that was now entirely her own. Her husband’s office, to her surprise, did not fill her with the awful sadness she felt in much of the rest of the house, maybe because it was the place where her husband had been so productive.

But his bedroom and kitchen brought pain, as did the ground-floor dining room. The Ebbets Field poster in his bedroom made her so sad she could not cross the threshold, and seeing the wingback chair in his kitchen never failed to depress her.

One day, about two months after her husband’s death, when her architect friend Adam Schoenhardt was visiting, she erupted. “I said, ‘See that chair, I can’t bear it,’ ” Ms. Parker says. “All I see is Bob sitting there glumly and staring at me.”

She did not want to get rid of the Sad Chair, so Mr. Schoenhardt removed it from her sight, to a corner of a little-used sitting room. Then, over a few days, he rearranged the rest of the house.

In some rooms, like the garden-level dining room, it was as simple as changing the position of the furniture. In Mr. Parker’s rooms — with the exception of his office, which remains unchanged — it was more extensive. The butcher-block counter where Mr. Parker ate was taken to the basement and replaced with a small dining table. His basement workout room, with punching bag, became a guest room. Mr. Parker’s bedroom was redecorated. His bloodied bed was replaced with a pine bed that had been in storage. The Ebbets Field poster went to a guest room in the basement.

The changes were disturbing to some. A man who had worked for the Parkers for several years at first refused to take the poster out of Mr. Parker’s room. Ms. Parker understood.

“When these cataclysmic events happen, you have no idea how you will react,” she says. “You can’t rehearse ahead of time. A couple of friends are widows, and I’ve tried to be supportive of them as they go through the grieving process, but in one case in particular, she grieved by creating a shrine out of the house. God forbid her husband’s shoes were not lying under the bed the way she wanted — she wanted everything to be exactly as he had left it. That was such an anathema to me. I was exactly the opposite.”

Later, in another conversation, she adds: “The struggle is, how do you find a way to be respectful of that person? To have the memories and still make it bearable, so I can live without shutting a bedroom door or burning a chair.”

The Sad Chair, after a few moves around the house, is now in Mr. Parker’s old bedroom, where its appearance has been changed with an orange throw and a pillow. Showing a visitor the room, Ms. Parker doesn’t even mention it. When the reporter calls her attention to this, she says she thinks it is because the chair, in its new place, has been “desensitized.”

“I can see that chair, and I don’t see him sitting in it, slumped,” Ms. Parker says. “It no longer has human qualities, and it no longer looks like Bob’s place to sit in misery as he would watch me feed the dogs.”

Mr. Schoenhardt’s redesign — which, Ms. Parker stresses, did not cost a thing, because it was simply a rearrangement — has lifted her up.

“He made me feel that I am not in this house of death, where such a sad thing happened, but a whole new house, a whole new landscape,” Ms. Parker says. “When I had to walk in the house the way it was, it was to sort of walk into the gray cloud. I would just feel pulled down. Now it’s transformed.”

She adds playfully: “I feel like I could be in someone else’s home altogether — although I love the furniture this person has and what good taste she has.”

A few days later, she sends a follow-up note.

“My epiphany was, it was all about CONTROL,” Ms. Parker writes. “I was powerless to prevail over the turmoil, fear, grief and uncertainty following Bob’s sudden death. Still am, to a lesser extent, but I can control, with the help of my gifted friend Adam Schoenhardt, the inanimate objects inside my house. So I move, lift, re-use, re-recycle, drag, discover things and in so doing actively transform my physical living space. And hope to Christ it empowers me to transform my emotional living space — at least, I can control this part of my new life.”

Eulogy for Robert B. Parker by his son, David

This piece was read aloud at Robert B. Parker's memorial service earlier this month.

I met my father in 1959 though I don't

remember our first moments together. Over the years, I thought I'd come to know him quite well, but I never really understood--until these last weeks--that he was really three different men.

I met my father in 1959 though I don't

remember our first moments together. Over the years, I thought I'd come to know him quite well, but I never really understood--until these last weeks--that he was really three different men.

The man known as Ace was the first: a charming, loutish, self-aggrandizing, cuddly, hard-drinking, sweet-talking, self-styled hooligan who used to tell us he'd one day become famous. We didn't believe him. It so happened he was right, because his second incarnation turned out to be Robert B. Parker, the venerated author who had restored a disreputable but quintessentially American genre--the detective novel--to its preeminent place in American fiction. He gave it relevance, he gave it probity and he gave it heat. For this, Robert B. Parker was beloved by millions and belonged really to the world.

The third man was Bob, and he belonged to us. Bob had been lurking inside Ace all along but Ace had to loosen his grip a little in order for Bob to emerge. While Bob posed little threat to the gadfly author jousting with talk show hosts and speaking in epigrams he was there inside Robert B. Parker too.

Bob Parker, was my father. He hated to be referred to as "my dad". He was my father. "My dad" always struck him (and me) as half-assed, slangy, casual--not befitting the grandeur of the office. He was very serious about being a father and believed it to be a great and marvelous undertaking. Oh, I called him "Dad" when we were together but when I spoke of him it was always as "my father".

We all know of his passion for social justice, civil rights and noblesse oblige, and because these traits are enshrined in his work, it's easy to take them for granted. But we've only to remember how hard-won they were. In building his character, he had to reject the narrow-minded and bigoted conservatism of his parents and his parochial upbringing. A larger life beckoned him. He dared to eat the peach. He rode away from his mundane origins on a kind of daft confidence that allowed him to transform himself as needed but without losing his center. In contrast, I didn't have to reject his values to build my character. I wanted to be like him.

He was upstanding. He quit his fraternity in college as a point of honor because it wouldn't admit black people or Jews. He took me as a fourth grader to civil rights marches and anti-war protests, he embraced feminism (though not without some irony), and later, although he recoiled from the pieties of identity politics, he came ardently to believe in marriage equality. His ardor was not based in politics which he found a malignant domain. Nor did he support it because it afforded people equal rights (though it does). He favored it because marriage itself was central to the romantic adventure that gave meaning and texture to his life. He knew that no one could honorably be denied so basic a pursuit of happiness. Those who lacked the rectitude to agree received, and deserved, his contempt.

On a more quotidian level, my childhood with him was often fraught. I was a somewhat dainty little boy who hated sports and often disdained his vulgarity. I danced smartly round the living room to television variety shows but I wouldn't have picked up a baseball bat at gunpoint. Just when I feared my nelly antics would cause him to recoil or withdraw, he would magically turn another side of himself toward me. My earliest memories of him are of a book of Renaissance paintings he gave me when I was a toddler. We poured over this book together and he told me the stories contained in the elaborate paintings. He decoded their symbols for me and together we consumed these works with an almost gastronomic relish. I felt immediately that this world of art was ours, his and mine.

He took me to Baseball games at Fenway Park where I sat slumped in the sticky seat, counting the seconds until it was over but he also took me often to the Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum where we would lose ourselves together in the hushed galleries filled with saints and knights. This sensitive aesthete so far from Ace was, I now think, the nascent Bob Parker whom I would come to know much better later. I like to think that he tried this person out with me and, though I was a child, I nurtured him.

He thought a civilized man ought to know at least a little bit about a lot of things, so when I was a teenager and decided that I wanted to dance, I asked him if we could go, for the first time, to a ballet performance. Now, we'd been taken often to the theater, but never to the ballet and I thought myself quite soigné for asking. My father, at that moment in a cut-off sweatshirt covered with muffin crumbs, bacon grease, Flintstones Jelly and beer stains replied without dropping a beat--"Yeah, I'd like to see something by Twyla Tharp, I understand she's quite innovative". I was shocked. How did he know about Twyla Tharp in the mid-seventies? Had he belched while saying it, it wouldn't have been more incongruous. Such was his ineffable breadth.

There were more challenges, our biggest came when I was 31, and I thought I probably shouldn't go through with my planned marriage to my longstanding girlfriend. It seemed increasingly plain to me that I needed to know the love of a man. I told my father this and he surprised me again, though not this time pleasantly. He was very disappointed and told me I needed to follow through with my commitment to marry and that it was a selfish, or maybe even cowardly thing to withdraw from the wedding. He said that if I needed to have affairs with men that I should handle that discreetly after I was married. That was that.

I knew he was wrong. Our relationship, once so close, shut down. He later, as he often did in such situations, sent me a long letter, admitting he was wrong. He said his disappointment came from his wish for me to duplicate and validate his choices--that he had, in essence, groomed me to live a life that reflected his. I pointed out that what he proposed I do was not remotely a life which reflected his, in ways which now seem comically obvious. I resolved to show him that my being gay was no impediment to building a life that testified to the things he and I cherished.

Let me count the ways:

Like his, my intimate relationships are abiding, loyal, deep and passionate. Like him, I think that what one does, one should do well. If we like eating we should eat well, we should cultivate our senses, we should dress well and learn what suits us, we should play at things that matter and not be idle or trivial. We should travel and know something of the world, we should learn another language. We should view all things, except romantic love, skeptically. We should puncture piety, challenge orthodoxy, we should be secular. We should be cultured without being effete, erudite without being pompous, smart without being glib. We should follow our own law consistently. People we love should know that we won't let them down. We should be funny.

One of my favorite parts of Dad was what I think of as his Lady Bracknell side. I write rather elaborate special thanks in my theater programs, the ones the audience reads during my shows, it's my way of doing what he did in the dedications for his books. His favorite of the ones I wrote to him was the following--" I thank Dad for his bottomless contempt". He loved that. He knew that no one's contempt ran deeper than his and that no one admired that more than me.

I want to wind down with a quote he used as the basis for the title of one of his Spenser novels. It's from Herman Melville's Moby Dick.

"And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he forever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar."

Goodbye Ace, Goodbye Robert B., Goodbye Bob, Goodbye Dad.

February 7, 2010

GUNS & POETRY

GUNS & POETRY